In an era where location data has become central to decision-making, infrastructure planning, and environmental management, the roles of surveyors, geospatial analysts, and drone pilots have grown not only in relevance but also in connectivity. These three professionals, although often categorized separately, now operate in a shared space where their tools, data, and expertise overlap significantly. The synergy among them is not just convenient it’s becoming essential for delivering fast, accurate, and meaningful geospatial solutions.

This post explores the relationship between these roles and how they collectively drive forward modern mapping, smart urban development, and spatial intelligence across a wide range of sectors.

The Surveyor: The First to the Field

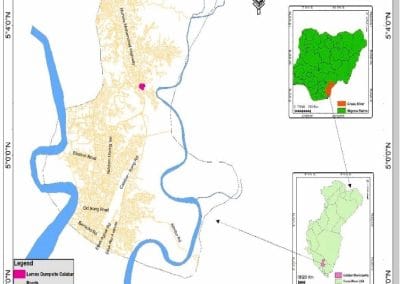

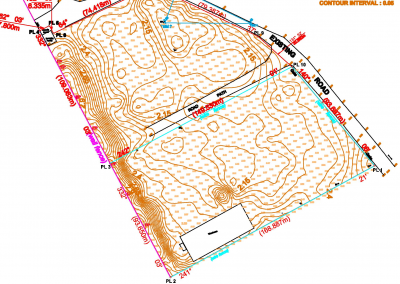

Surveying is one of the oldest professions in the built environment, yet it remains at the forefront of spatial accuracy and control. Surveyors are typically the first professionals on-site, responsible for setting the geometric and positional foundation for all other spatial activities that follow. Their work involves measuring distances, angles, elevations, and coordinates using high-precision instruments such as total stations, GNSS receivers, and digital levels.

What sets surveyors apart is their deep understanding of spatial reference systems, geodetic control, and measurement science. They ensure that all other datasets including those captured by drones or used in GIS are tied to real-world coordinates. In many projects, surveyors provide the ground control points (GCPs) that make drone imagery and remote sensing data accurate and usable for detailed analysis.

More importantly, surveyors are trained to assess the land in a practical context identifying property boundaries, understanding terrain constraints, and ensuring legal and engineering standards are maintained. Without this foundational role, even the most sophisticated drone-captured or GIS-analyzed data can drift into inaccuracy.

The Drone Pilot: Expanding the Horizon

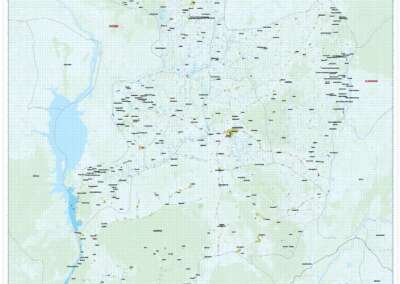

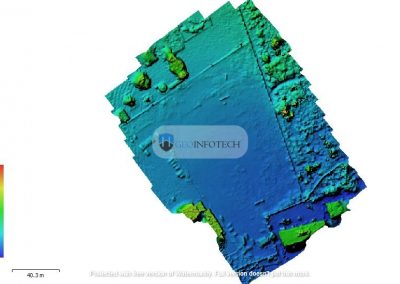

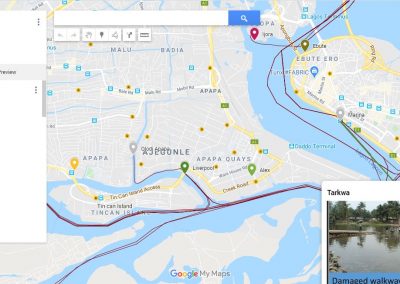

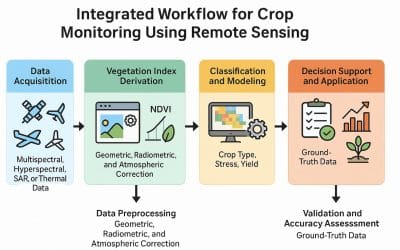

The rise of drone technology has dramatically shifted how spatial data is collected. Equipped with high-resolution cameras, LiDAR sensors, and thermal imaging devices, drones are now essential tools for surveying, agriculture, construction monitoring, and environmental assessment. A drone pilot doesn’t just operate the equipment they plan flight missions, understand terrain conditions, handle georeferencing logistics, and comply with airspace regulations.

In the field, drone pilots can collect large volumes of data in a fraction of the time it would take for traditional methods. This is especially useful in areas that are vast, dangerous, or difficult to access. By flying automated missions, drone pilots gather imagery and point clouds that are later processed into orthophotos, digital elevation models (DEMs), and 3D terrain reconstructions.

However, drones are not autonomous agents of accuracy. Their data must be grounded and that’s where surveyors come in with their ground control points, and geospatial analysts follow to make sense of the visuals. The drone pilot, in this triangular relationship, is the eyes in the sky, bringing a broader perspective that complements what’s happening on the ground.

The Geospatial Analyst: Turning Data Into Meaning

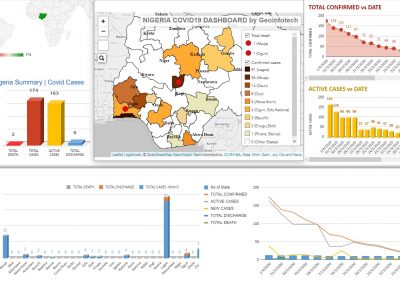

Once data has been collected from the field whether by the surveyor or the drone pilot it needs to be transformed into maps, statistics, models, and interpretations. That’s the domain of the geospatial analyst.

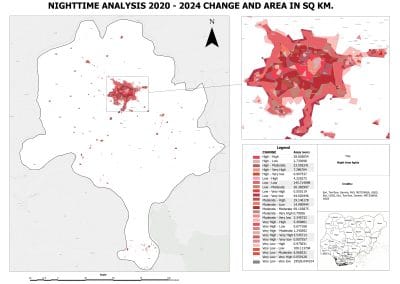

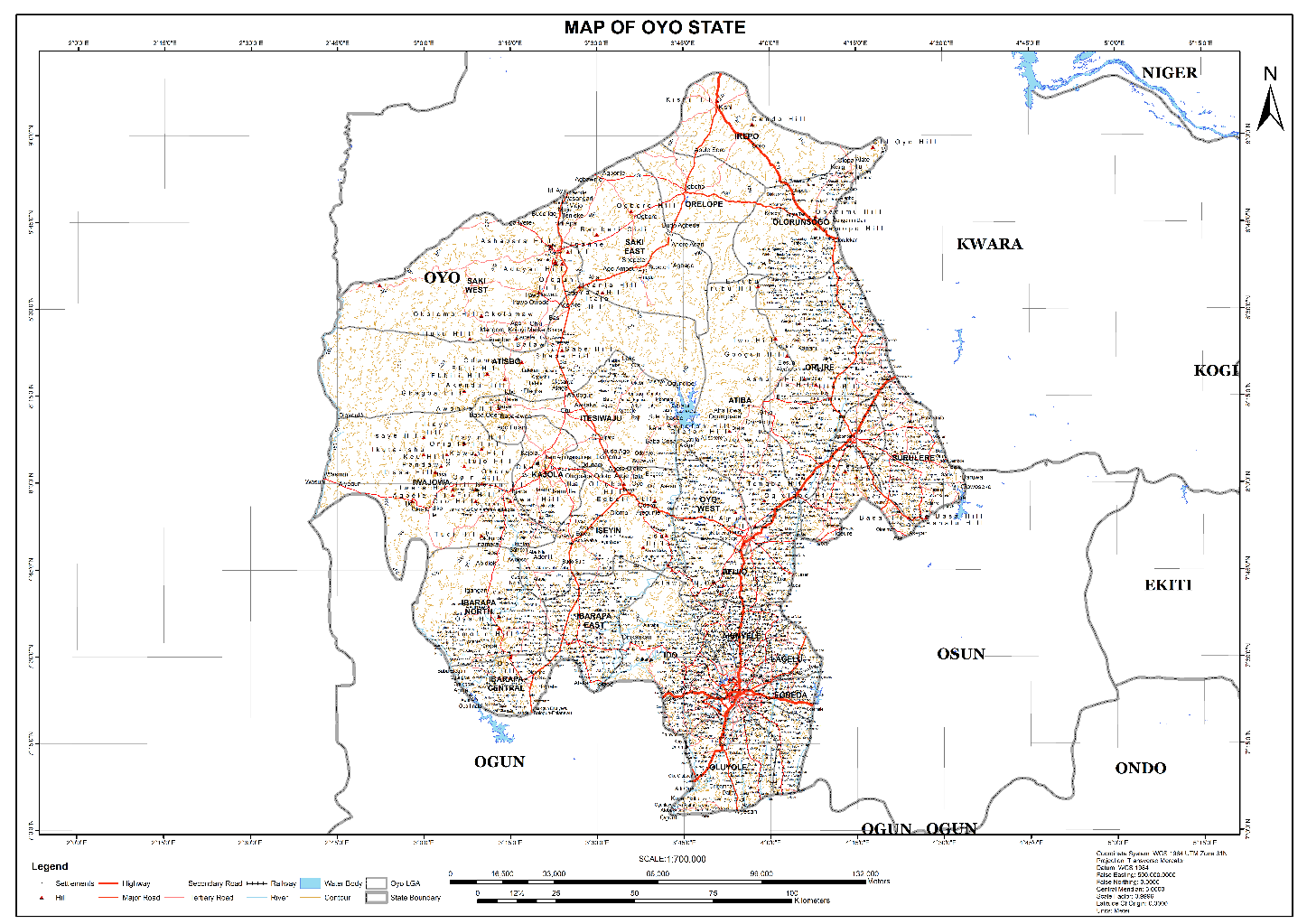

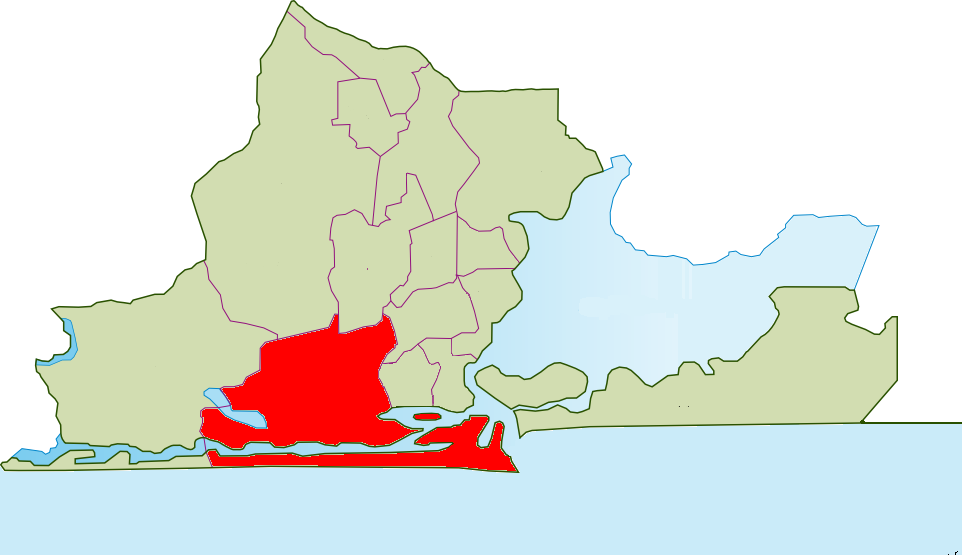

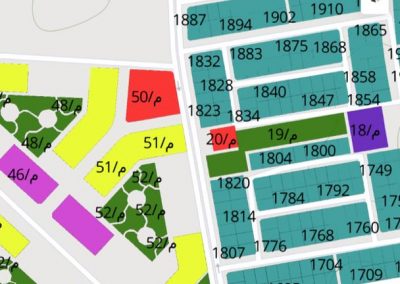

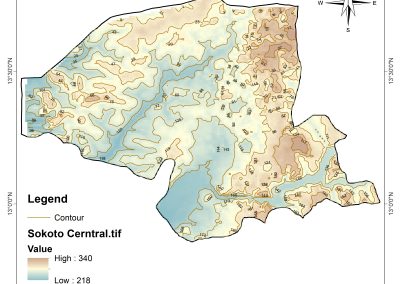

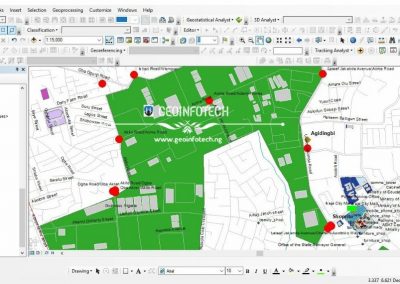

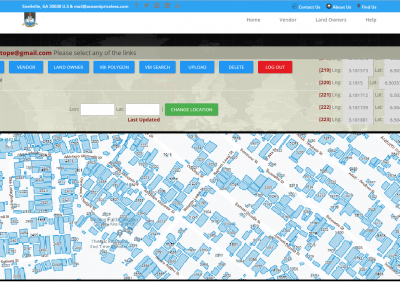

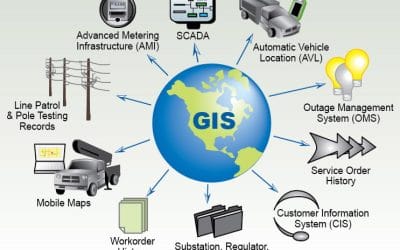

A geospatial analyst uses GIS software, remote sensing tools, and spatial algorithms to extract insights from data. Their work ranges from simple visualizations like land use maps to complex spatial modeling for flood prediction, urban growth simulation, or resource allocation. They apply techniques like overlay analysis, interpolation, suitability analysis, and geostatistics to answer location-based questions.

What makes the geospatial analyst essential is their ability to contextualize data. While a drone pilot provides the imagery and a surveyor provides the coordinates, the analyst puts the pieces together, often integrating external datasets like census data, road networks, environmental layers, and satellite imagery. Their goal is to generate knowledge that supports planning, policy, or engineering decisions.

In multi-disciplinary projects such as urban planning, renewable energy siting, or infrastructure design geospatial analysts become the translators between raw data and informed action. Their role often sits at the center of collaboration, making them an anchor in the trio of spatial professionals.

Where Their Work Intersects

Though their tasks differ, surveyors, drone pilots, and geospatial analysts are part of a seamless spatial workflow. Consider this simplified sequence in a real-world scenario:

- A surveyor establishes the reference system and base points on the ground.

- A drone pilot uses those points to georeference aerial imagery and collects data over a wide area.

- A geospatial analyst processes this imagery, combines it with other spatial datasets, and produces actionable outputs like suitability maps or infrastructure plans.

None of these steps can stand alone. If the drone data is not well-aligned with the ground, the analysis could be flawed. If the analysis is poorly conducted, even the most accurate data becomes meaningless. If the survey control is off, the entire dataset could be spatially incorrect.

Each role adds value to the data pipeline — surveyors bring precision, drone pilots bring speed, and geospatial analysts bring intelligence. Together, they provide a holistic solution that serves industries ranging from real estate and agriculture to environmental conservation and emergency response.

Conclusion: A Collaborative Future

As our cities grow smarter and the demand for real-time, location-based information increases, the intersection between surveying, drone technology, and geospatial analytics will only deepen. What once seemed like separate professions are now complementary gears in the same spatial engine.

For students and professionals in any of these fields, learning to collaborate across disciplines is no longer optional it is the new standard. The more you understand how your work fits into the bigger geospatial picture, the more valuable and effective you become.

In essence, the modern geospatial landscape is a collaboration zone, not a silo. Whether you are on the ground with a prism, above the ground with a drone, or behind a screen analyzing pixels, you’re contributing to the same goal building a clearer, smarter, and more responsive understanding of the world we live in.